Quick Tips

Resources

Standards

Maya the Exhibition I: Daily Life & New Discoveries is the first of two virtual field trips. In Maya I, discover the agricultural innovations the Maya used to build cities in a rainforest, the factors that led to the collapse of the Classic Maya population, and how the society transformed to survive today.

This exhibit is a cooperation with Museums Partner and Patrimonio Natural y Cultural, supported by the Ministry of Culture and Sports in Guatemala. Lenders of the objects are “The National Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology" and "The Ruta Maya Foundation" in Guatemala.

ADVENTURE ROADMAP

Immerse yourself in the genius of the Maya, an urban civilization that grew from the tropical rainforest. At the height of this civilization, the Maya lowlands were the most densely populated region on the globe. How did they create such an empire, why did it decline and how does it live on today in the millions who carry on Mayan languages and traditions?

Join Cincinnati Museum Center and researchers from the University of Cincinnati and University of Bonn to study Maya agriculture, engineering and power structures through stunning artifacts and intriguing finds.

LIFE IN A TROPICAL RAINFOREST

The ancient Maya lived deep within the tropical rainforest, which provided food, medicine and building materials. The forest also shaped Maya identity. Discover how the Maya utilized the forest and developed new forms of agriculture to feed their growing population.

DECLINE AND RISE

Why did the Maya abandon their lowland cities? Observe how community conflict, climate change and environmental damage led to the rise of a new civilization.

NEW DISCOVERIES

Breakthroughs from University of Cincinnati and University of Bonn researchers reveal details about how ancient Maya people perceived the world around them and managed their land, forest and water resources.

KAWINAQ - WE ARE STILL HERE

Maya culture lives on. “Kawinaq,” they say. “We are still here.” See how the Maya retain a strong sense of identity and culture in our globalized world.

MEET THE EXPERTS GUIDING YOUR VIRTUAL FIELD TRIP!

Dr. Nikolai Grube

University of Bonn, Germany

Dr. Nicholas Dunning

University of Cincinnati, Ohio

Dr. David Lentz

University of Cincinnati, Ohio

Dr. Sarah Jackson

University of Cincinnati, Ohio

Dr. Christopher Carr

University of Cincinnati, Ohio

Mariana Vázquez Alonso

PhD Candidate, University of Cincinnati, Ohio

Rebecca Nava

Artist and Educator

Héctor Rolando Xol Choc

Linguist - Q’eqchi’ speaker

LIFE IN A TROPICAL RAINFOREST

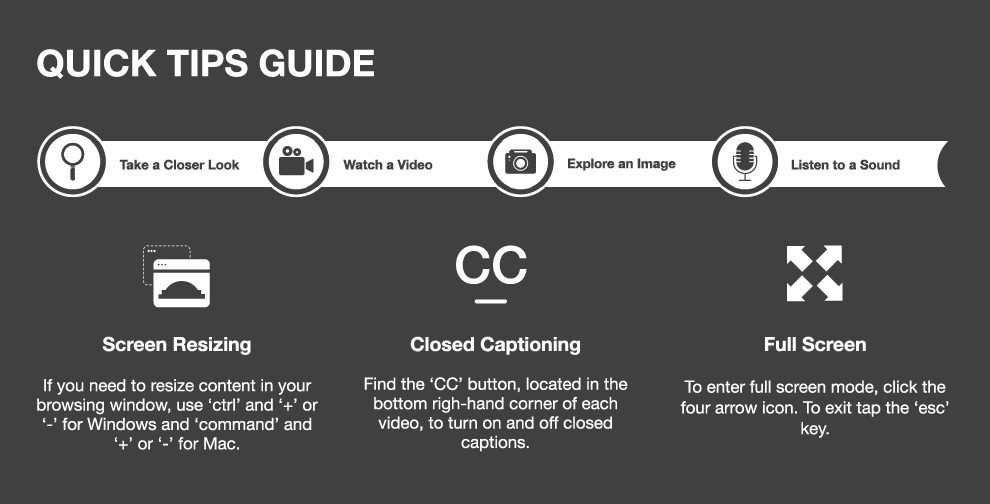

Click on the magnifying glass to explore more!

English

Español

Click on the video icon to explore more!

The ancient Maya lived deep within the tropical rainforest, which was a source of food, medicine and building materials. The forest also shaped Maya identity. Villages grew into large cities, each with a royal palace at its heart. The Maya built artificial lakes to collect water. With this infrastructure, combined with household gardens that produced food inside the cities, as many as 100,000 people could live in one place.

Think of a major city and imagine all the things its citizens require. Every day they need food, water and shelter – and these things take work to maintain. Nobles and members of the rising middle class managed this work; traders, artisans and warriors helped and prospered. As populations grew, so did the cities. The Maya needed more and more land to supply people’s needs. They expanded their cities into the wild, building farther and farther into the surrounding rainforests.

BUILDING RESERVOIRS

The Maya developed new forms of agriculture. They created terraced fields on hilly terrain. They set low stone walls into the sides of hills to prevent erosion and keep fertile soil in place. These terraced fields increased the yield of maize and allowed the Maya to grow cotton and other crops.

The Maya built channels between periodically flooded swamps to water crops. This helped them harvest several times each year. They also turned abandoned quarries into farming plots. When massive limestone blocks were removed for building projects, fertile soil and water accumulated. The Maya used this land to grow plants – such as cacao, the tree used to make chocolate – that needed nutrient-rich soil.

AGRICULTURE

The Maya landscape was far from ideal for growing food, yet the Maya were able to provide balanced nutrition for millions of people. First, they had to choose and clear a site, and then leave it to dry over winter. In spring, the farmer would burn the dried site so that the fire’s ashes could mix with rainwater and fertilize the thin tropical soil. Careful timing was crucial: a fire set too late might be extinguished by the first rain, but ash from a fire set too early might be carried away by the wind.

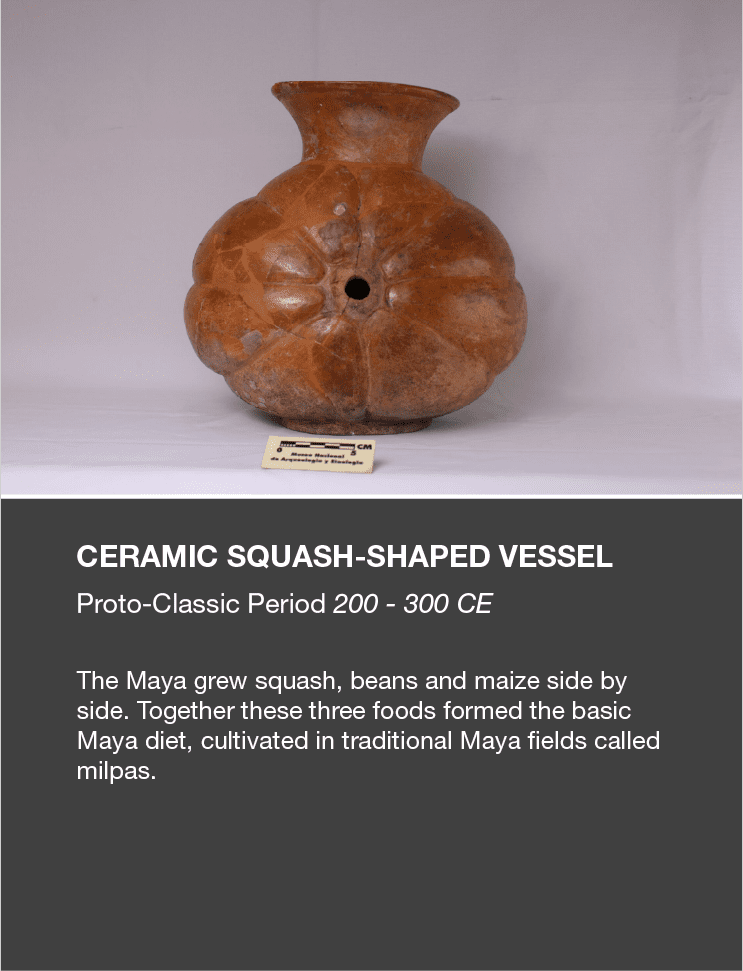

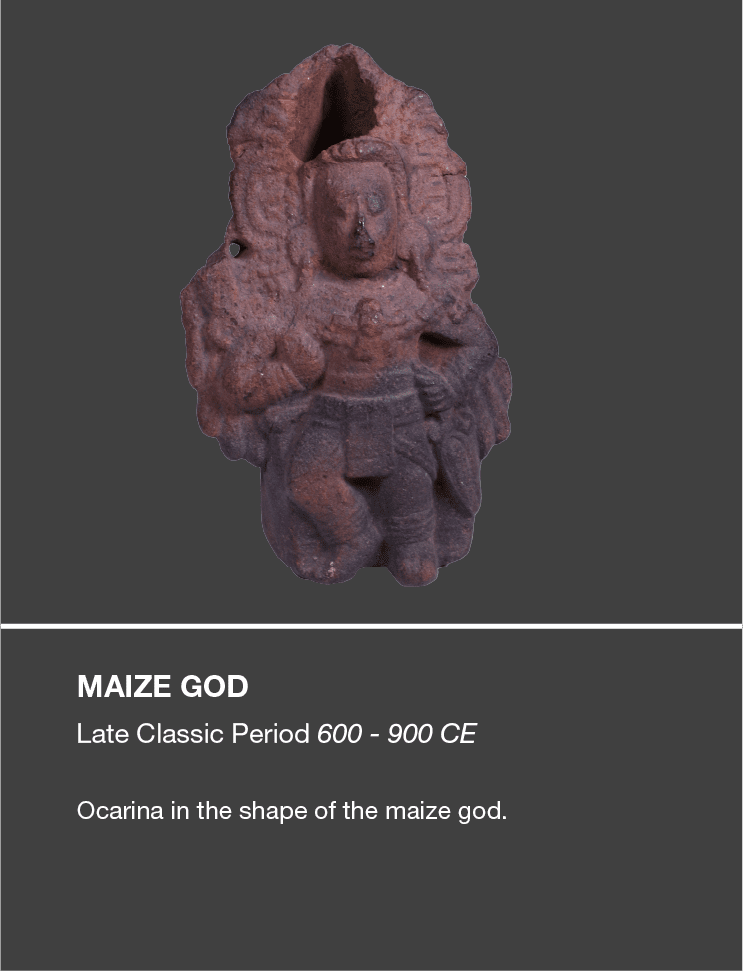

The Maya put certain plants together to improve soil chemistry and use their space wisely. Planting corn, beans and squash together helps each plant grow: the cornstalk becomes a pole for bean and squash vines, bean plants give soil the nitrogen it needs and the squash plant’s broad leaves provide shade to help the soil retain moisture. Maize – or corn – was more than a crop for the Maya people.

They had a deep love for the maize plant and the maize god, who was always portrayed as a beautiful young man with long hair. They might also grow different types of beans, squash, sweet potatoes, yucca, jicama and chilies. To supplement what they farmed, the Maya collected honey and medicinal plants, extracted fibers from palm and kapok trees, pressed oil from nuts and ate wild fruits from the nearby rainforest.

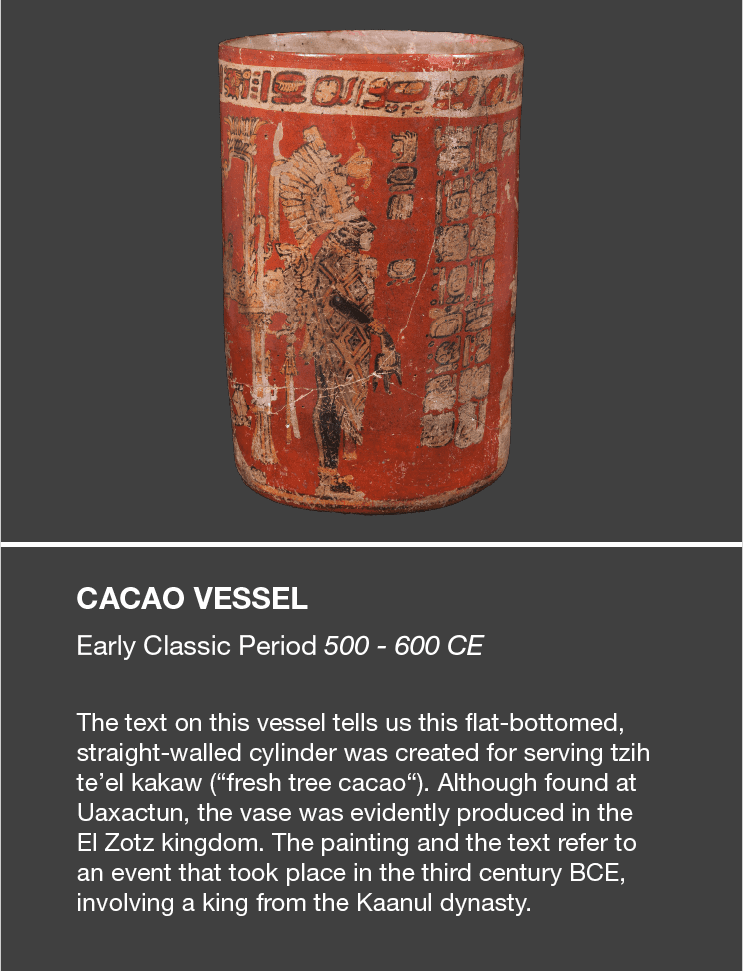

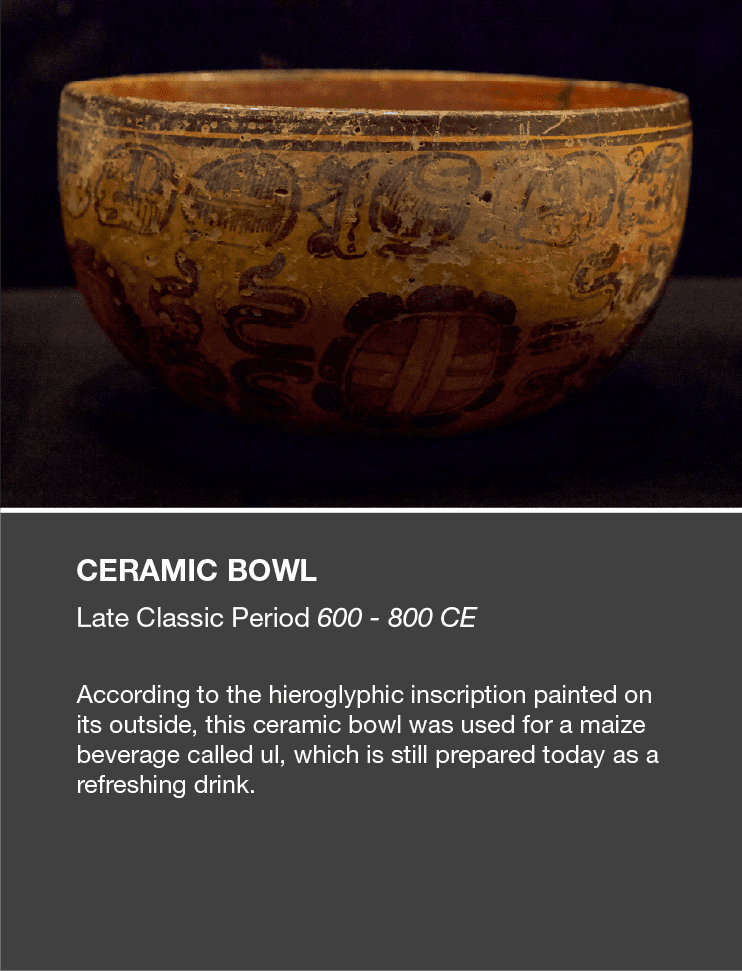

After securing their nutritional needs, the Maya grew cacao – the base plant for chocolate – as a luxury food. They used cacao beans to season foods and make chocolate drinks, improving the raw bitter taste with chili powder, vanilla and maize. The Maya served liquid chocolate at weddings, funerals and royal occasions – often in elaborately decorated cups that expressed the hosts’ wealth and status. Chocolate became so valuable that the Maya even used cacao beans as a form of currency.

As their population grew, the Maya developed new forms of farming to feed more people. They terraced fields to grow more food, maintain healthier soil and grow cotton and other cash crops. Today, we can still see the remains of these terraces in the Maya lowlands – and farmers still use the Maya’s agricultural innovations.

TRADE

Click on the magnifying glass to explore more!

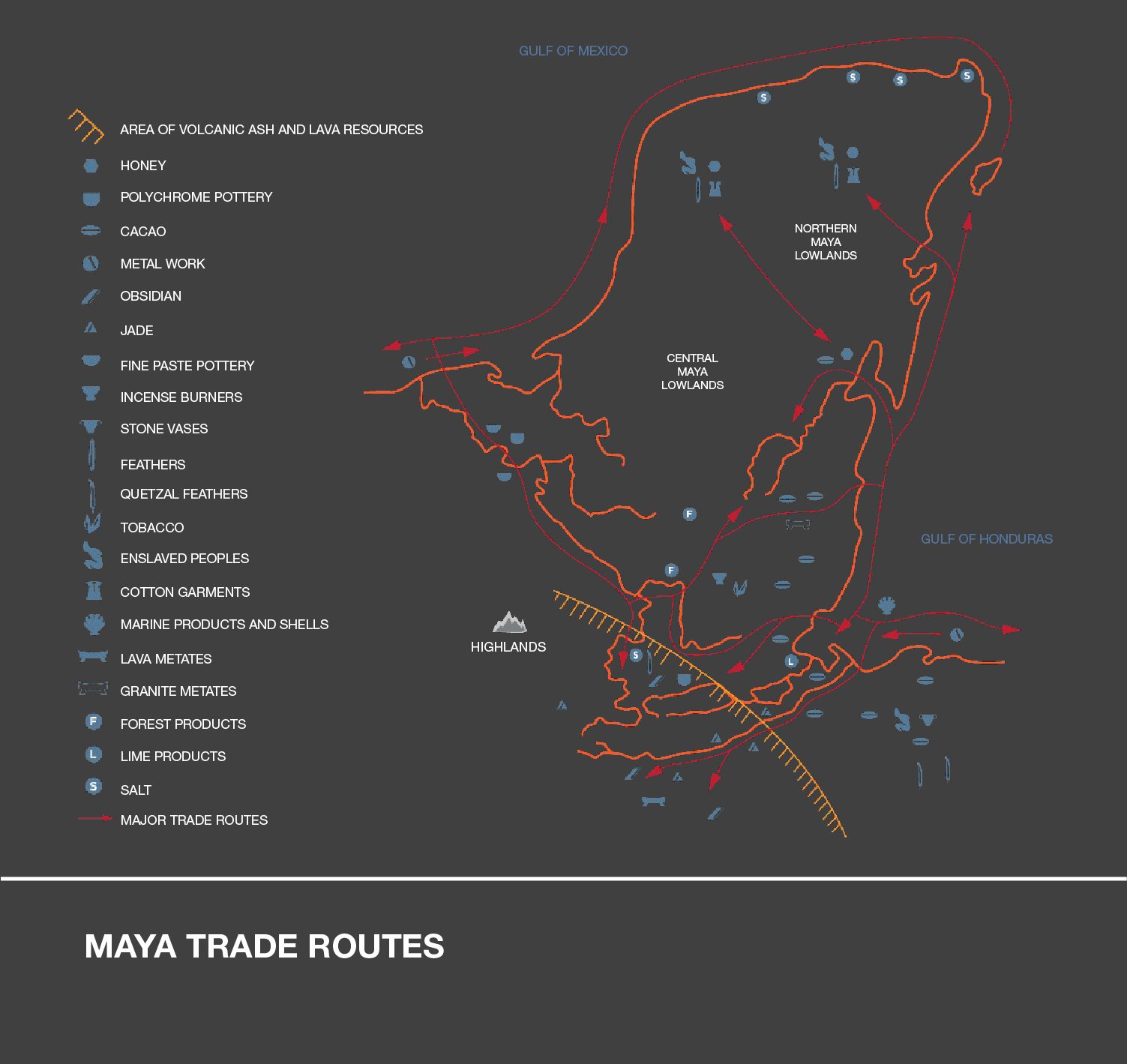

The Maya planted luxury crops, such as cacao, for consumption and trade, which they used to grow their economy. The lowlands were fragmented into several competing small states. The Maya packed trade goods into baskets and backpacks, traveling the rainforest trails on foot. They paddled canoes down rivers and along coastlines. In this way, they established extensive trade networks that connected the Maya lowlands with the highlands of Guatemala, the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea.

DECLINE AND RISE

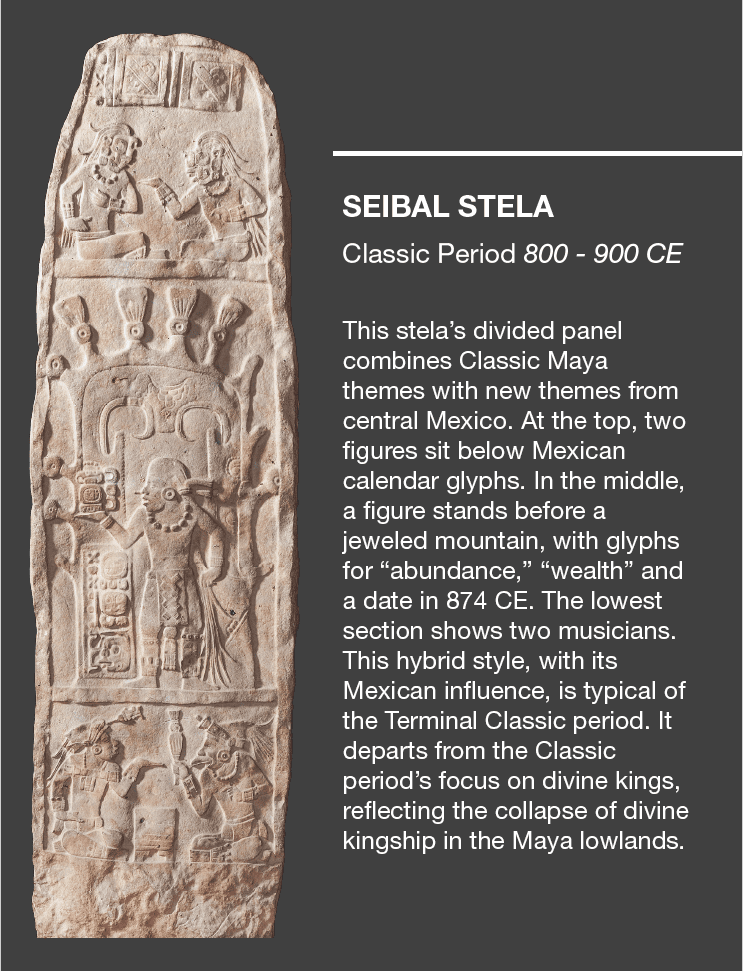

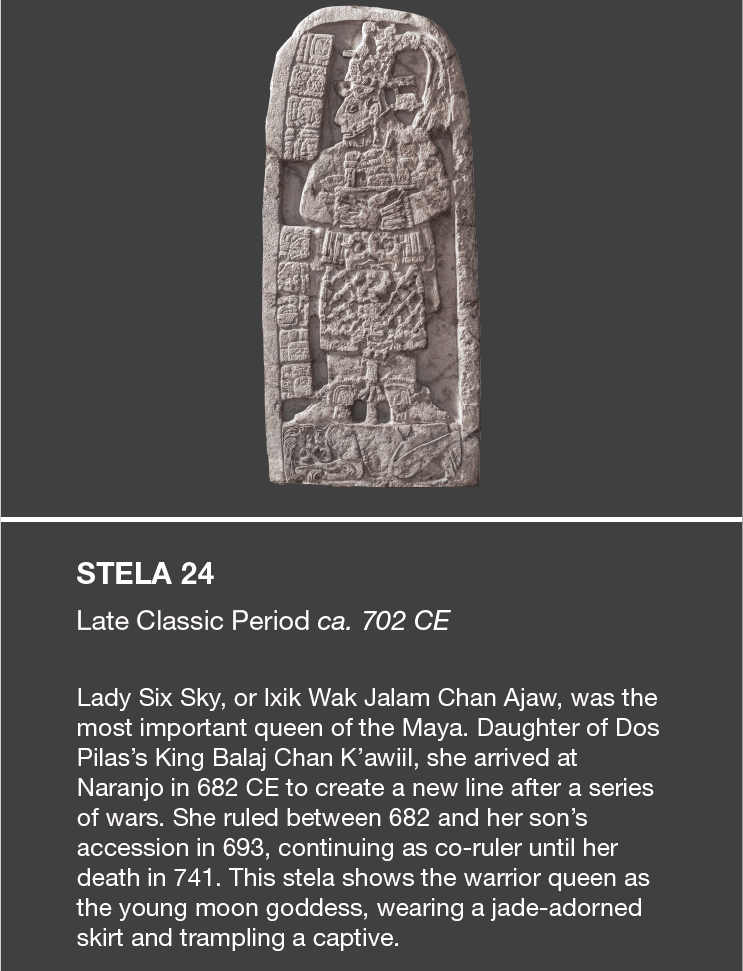

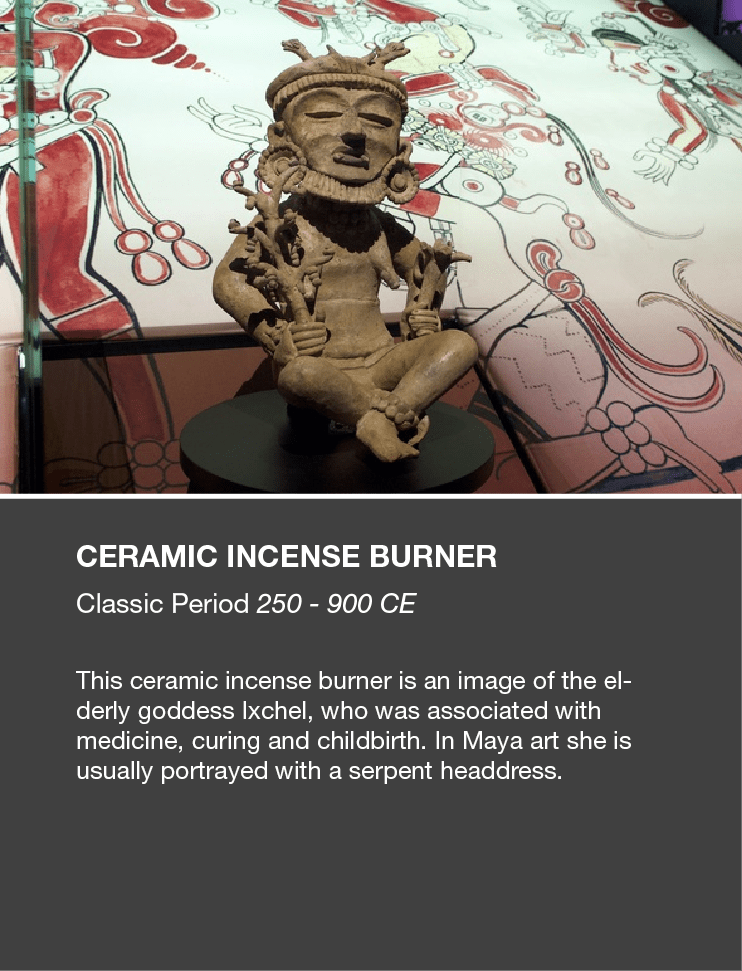

Maya culture prospered during the Classic Period, 250-800 CE. During times of peace and prosperity, the arts and sciences flourished. The Maya grew their understanding of the world around them, becoming skilled at mathematics and astronomy. Kings were no longer mere mortals—they had become divine beings with supernatural powers.

But the peaceful times were disrupted by war after war. Rulers fought over trade routes and natural resources for their growing populations. Cities rose and fell. By 700 CE, the entire Maya world was governed by two superpower cities—Tikal and Calakmul. When these powers collapsed, too, this golden age came to an end.

THE GREAT COLLAPSE

Prolonged warfare destroyed a social and government structure that had been effective for millennia. When cities fell, the Maya were left without governments or reliable sources of food, water or work. Around 800 CE, climate change brought long periods of drought, and populations began to starve. Research from the University of Cincinnati has discovered that water sources were also contaminated. When people left Tikal and Calakmul for the more fertile northern lowlands, the jungle reclaimed their massive stone cities.

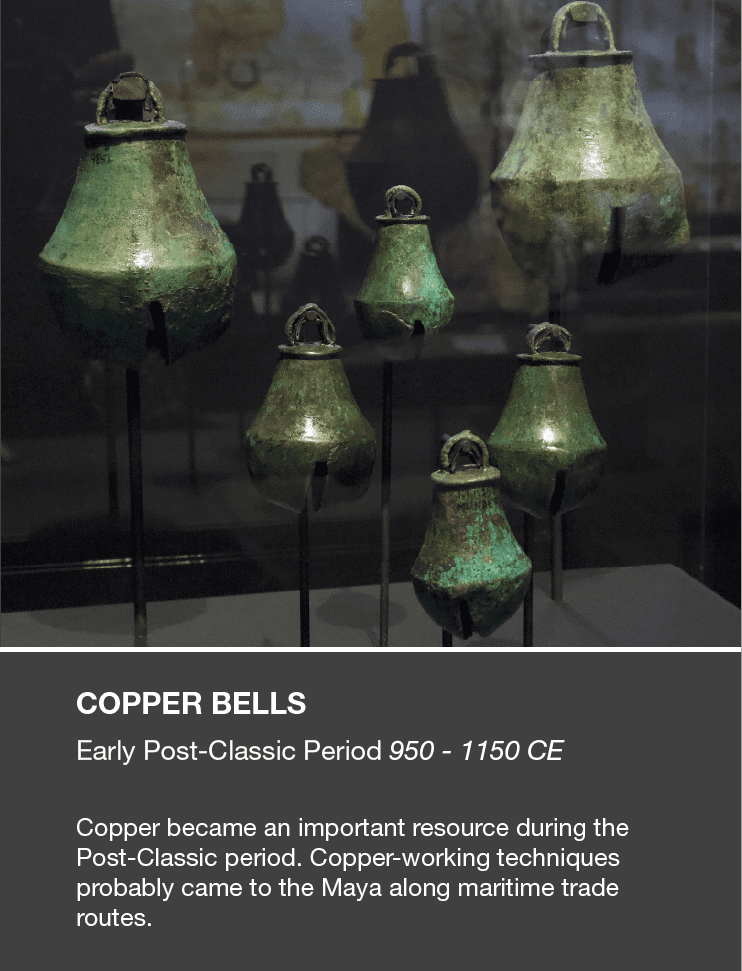

From around 800 CE onward, large parts of the Maya population moved from the lowlands to areas less affected by conflicts. Many people fled to the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico, where they mingled with the local population. The city of Chichen Itza became the most powerful metropolis of the early Post-Classic period.

In the 16th century, the arrival of Europeans introduced new religions, brought diseases like smallpox and flu, for which the Maya had no immunity; and the result was a dramatic decrease in population. By beginning of the 17th century, only 10% to 15% of the pre-Columbian population survived.

A NEW CIVILIZATION RISES

For a time, Chichen Itza was the largest and most economically powerful city in the Maya empire. Between 900 and 1100 CE, 50,000 people lived in and around the city. Eventually, the city of Mayapan acquired Chichen Itza’s trade routes. Mayapan soon grew into an empire that included the entire Caribbean coast. Like Chichen Itza, Mayapan was governed by a collective of noble families. These families shared some of their wealth with others, giving rise to a middle class who could buy goods and drive a strong economy.

In the 16th century, the arrival of Europeans introduced new religions, brought diseases like smallpox and flu, for which the Maya had no immunity; and the result was a dramatic decrease in population. By beginning of the 17th century, only 10% to 15% of the pre-Columbian population survived.

Despite the drastic decline in population, the Maya would survive the great political and social transformations after the downfall of their cities, just as they would survive the trauma of the Spanish conquest.

NEW DISCOVERIES

Breakthroughs from University of Cincinnati researchers reveal details about how ancient Maya people perceived the world around them and managed their land, forest and water resources. UC’s innovative research techniques and fieldwork have helped us understand how the ancient Maya planned their cities, and why the Maya abandoned these sites in the 9th century. The work of UC researchers and their collaborators helps us understand ancient Maya culture and people.

Google Map: Identified are past and ongoing research projects, conducted by researchers from the University of Cincinnati.

RESEARCH BREAKTHROUGH: LIDAR

Click on the video icon

to explore more!

Light Detection And Ranging (LIDAR) uses lasers, carried by an airplane or helicopter, to project light toward the ground. Sensors capture information about the reflected light, creating a detailed 3-D representation of the earth's surface. University of Cincinnati researchers have used LIDAR to uncover patterns in how the Maya managed land and water in their cities and homes.

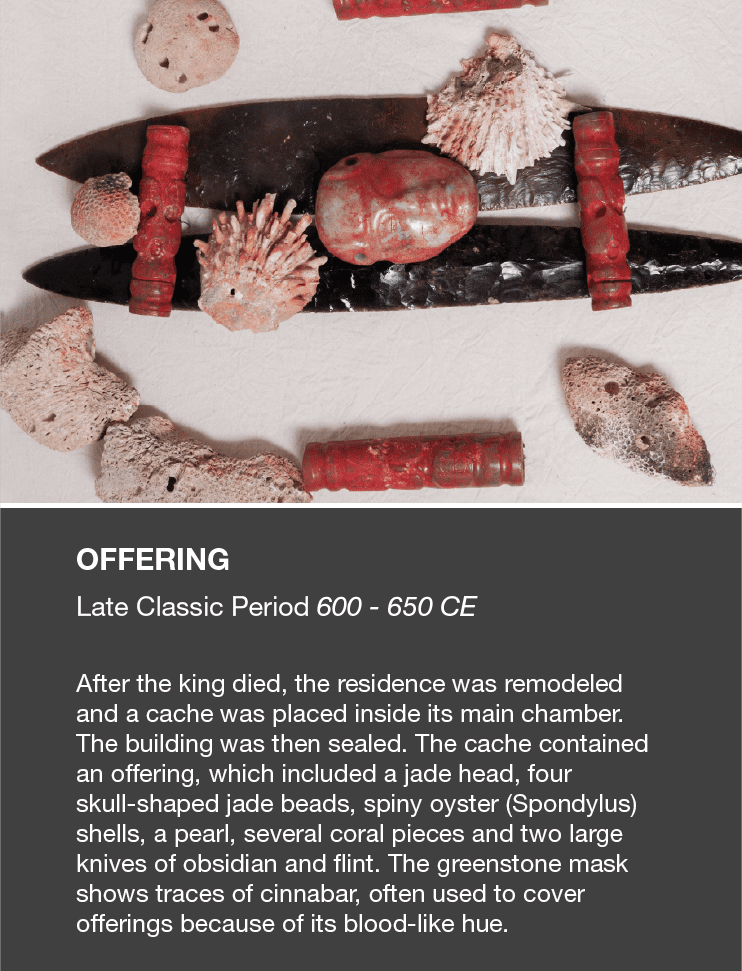

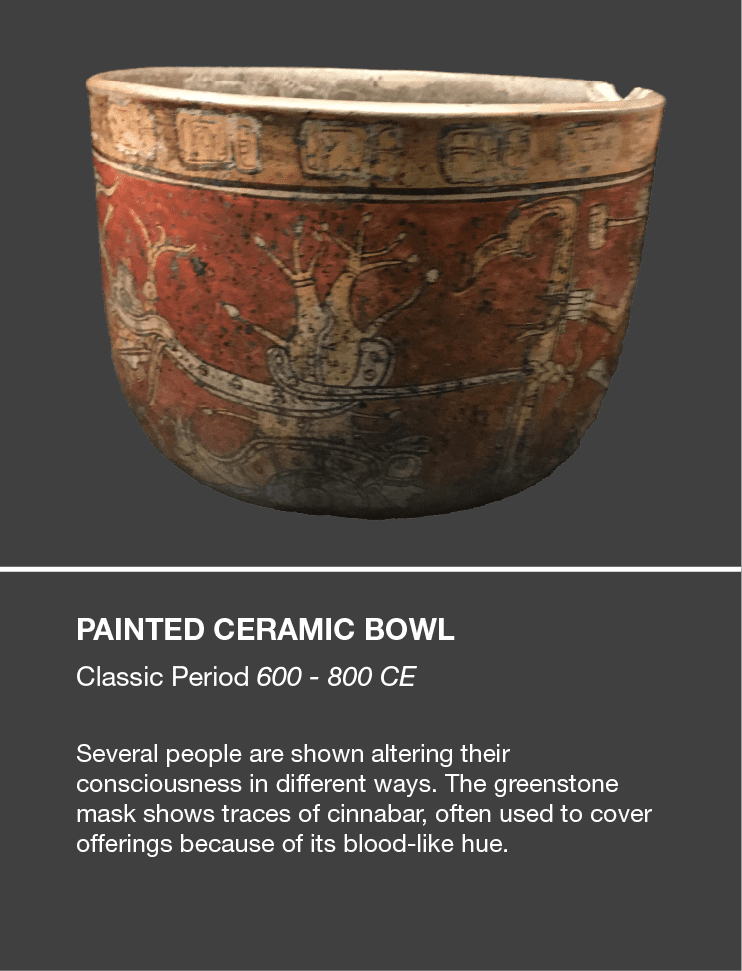

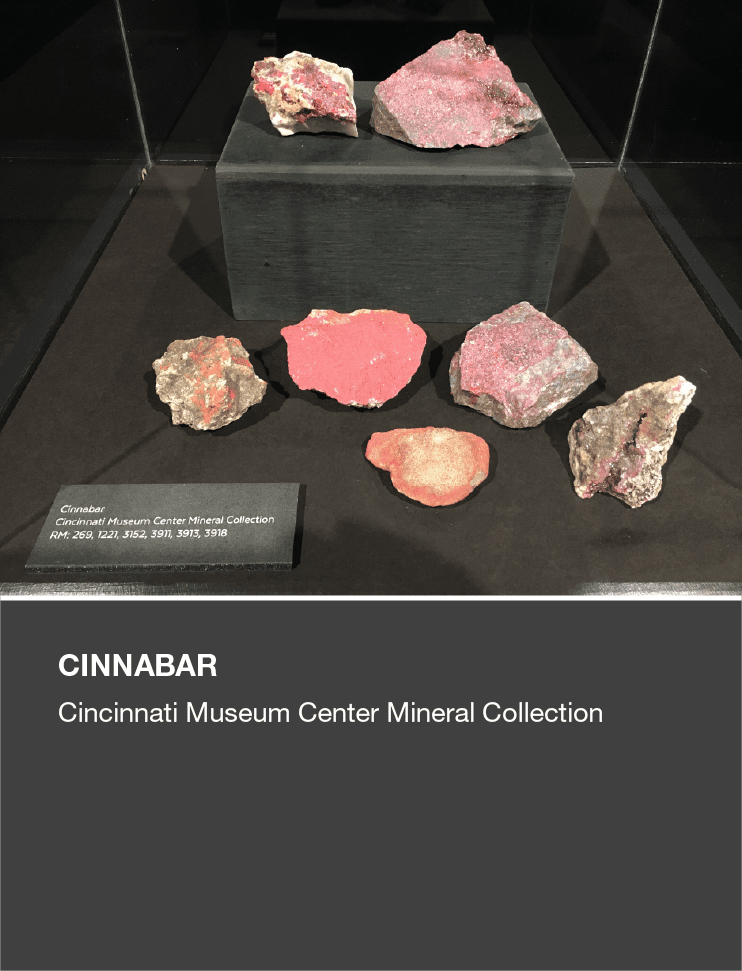

RESEARCH BREAKTHROUGH: CINNABAR

Click on the video icon

to explore more!

Maya ground up this red mineral and incorporated it into paint for their buildings. It lent a beautiful color, but also carried poisonous mercury with it. Rain washed it from buildings and into water supplies, and droughts concentrated it into city reservoirs. This combination of factors may have poisoned the Maya who used the water. UC researchers are currently studying to see whether a lack of fresh, clean water may have been a key factor in the abandonment of the city of Tikal.

Dr. Nicholas Dunning

Professor of Geoarchaeology & Neotropical Landscapes

“Many ancient Maya cities became victims of the so-called ‘reservoir effect.’ Urbanization was made possible by capturing and storing rainwater using increasingly sophisticated methods. Further population growth necessitated storing increasing amounts of water. Those large populations then became even more vulnerable when the region was afflicted with drought: the urban water supply was insufficient, and its quality declined.”

Dr. David Lentz

Professor of Biology and Executive Director of the University of Cincinnati Center for Field Studies

“Research at Cerén, a Maya village in El Salvador, showed that manioc was commonly used, but it was previously undetected because it doesn’t preserve well. The Cerén site, sometimes called the ‘Pompeii of Central America,’ was covered with volcanic ash around 600 CE. The ash preserved the houses, artifacts and even the agricultural fields amazingly well. As they were digging, the Cerén archaeological team found holes in the ash just before they reached the ground surface. When they filled these holes with dental plaster, it turned out that these holes were impressions of crop plants left in the fields. It turned out that there were extensive fields of manioc planted by the Maya, so it must have been an important food for them! This discovery has changed the way we think about ancient Maya agriculture.”

Dr. Sarah Jackson

Professor of Anthropology

“Studying the past is exciting because it challenges you to think about how life would have been different in another time and place. When I started to realize that the categories we use as archaeologists were not the same ones that the ancient Maya would have used to describe the same materials, I got really excited. This was an opportunity to use data, including texts and images, to reconstruct elements of how the ancient Maya experienced the world around them. The result makes the work of archaeology more inclusive of multiple perspectives!”

Dr. Christopher Carr

Research Assistant Professor of Geography

“One of our main geography questions is defining what the ancient Maya found attractive in bajos — these seemingly unattractive swamps. LIDAR makes it much easier to navigate this tricky terrain, and I, at least, don’t consider the swamps as forbidding as many of the old-timers led me to believe.”

Dr. Nikolai Grube

Curator of Maya: The Exhibition and Professor of Ancient American Studies and Ethnology at the University of Bonn, Germany.

Want to hear more from our experts? University of Cincinnati colleagues share additional insights about their research and careers.

INCREASING DIVERSITY IN ARCHAEOLOGY

Dr. Jackson shares her passion for ensuring the field of archaeology features voices from women and multiple ethnic identities to define more well-rounded questions to answer questions about the past.

CATEGORIES: FLIP BOARDS

Dr. Jackson discusses how the Maya have both similar and different ways of describing objects and seeing the world.

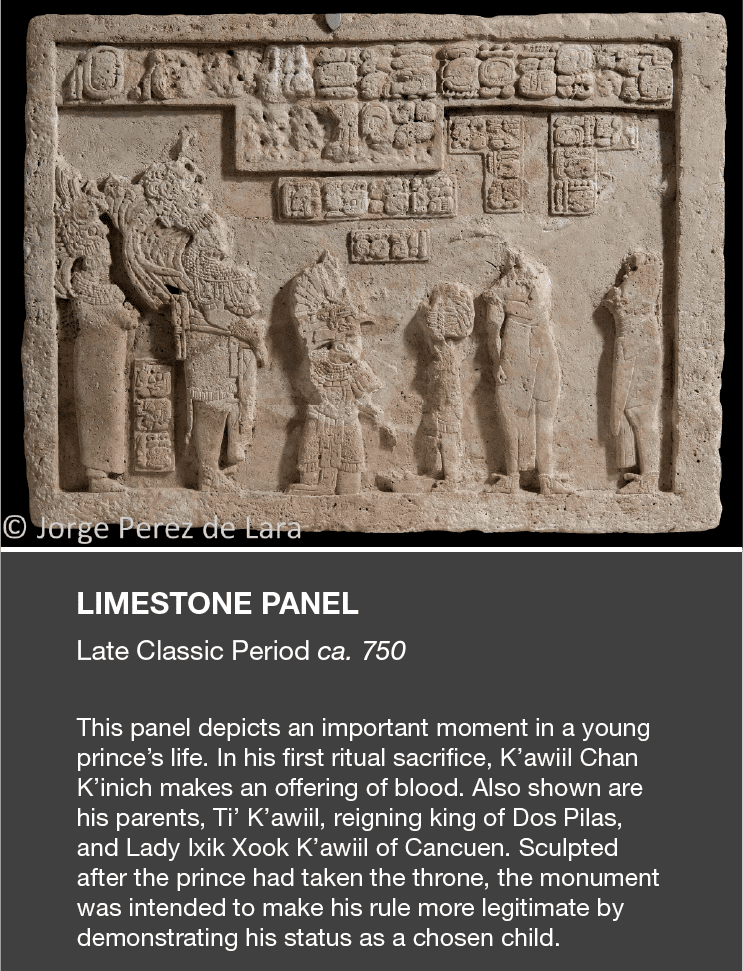

CANCUEN KING PANEL

Dr. Jackson helps us imagine the steps from discovering an artifact to what we see exhibited in a museum.

CANCUEN GLYPH PANEL

Dr. Jackson shares how the act of drawing helped her look at the text differently and how she brings together information from multiple sources to advance new understanding.

GEOLOGY VS ARCHAEOLOGY

Dr. Carr discusses how his role as a geographer complements the role of archaeologists.

RESEARCH IN A HOLE

Dr. Carr describes the work that takes place in the excavation pits of Maya reservoirs.

INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES

Dr. Carr discusses the importance of involving experts from multiple fields to support research.

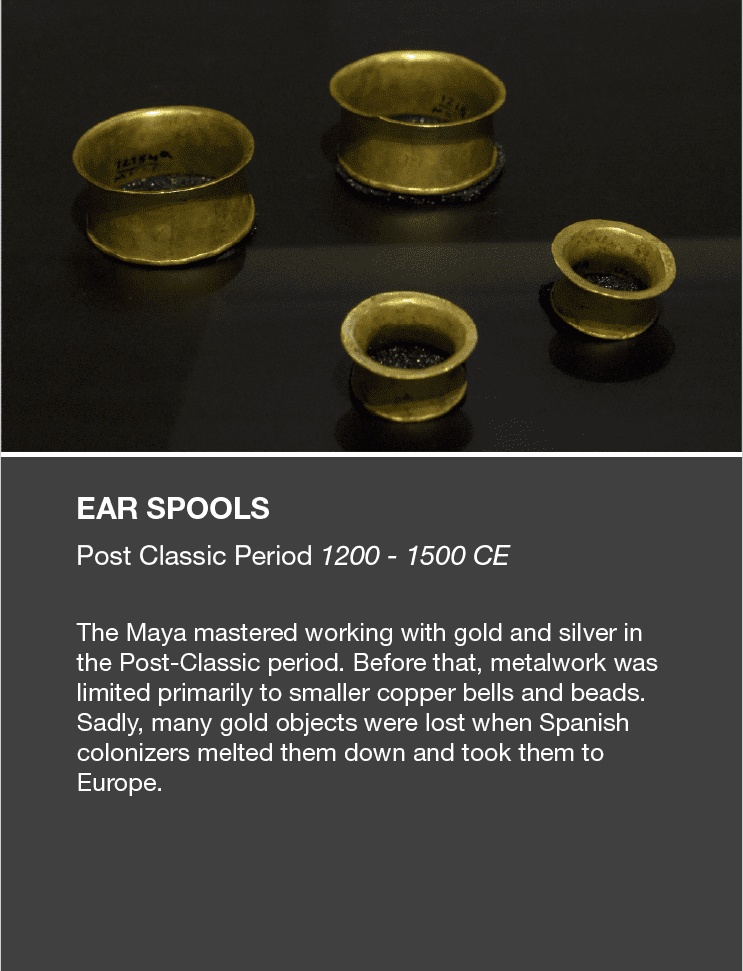

KAWINAQ - WE ARE STILL HERE

The close of the Classic Maya period meant the end of divine kingship and urban, courtly culture – but it did not mean the end of Maya people. The Maya survived great political and social transformations after their system of cities collapsed—just as they later survived the trauma of the Spanish invasion. Today, more than six million Maya descendants live in Mexico and Central America. Though they have lost their territories to industrial farming and mining, they move on, planting their seeds in new soil. Strong, resilient and adaptive, the Maya keep going. They have much to teach us.

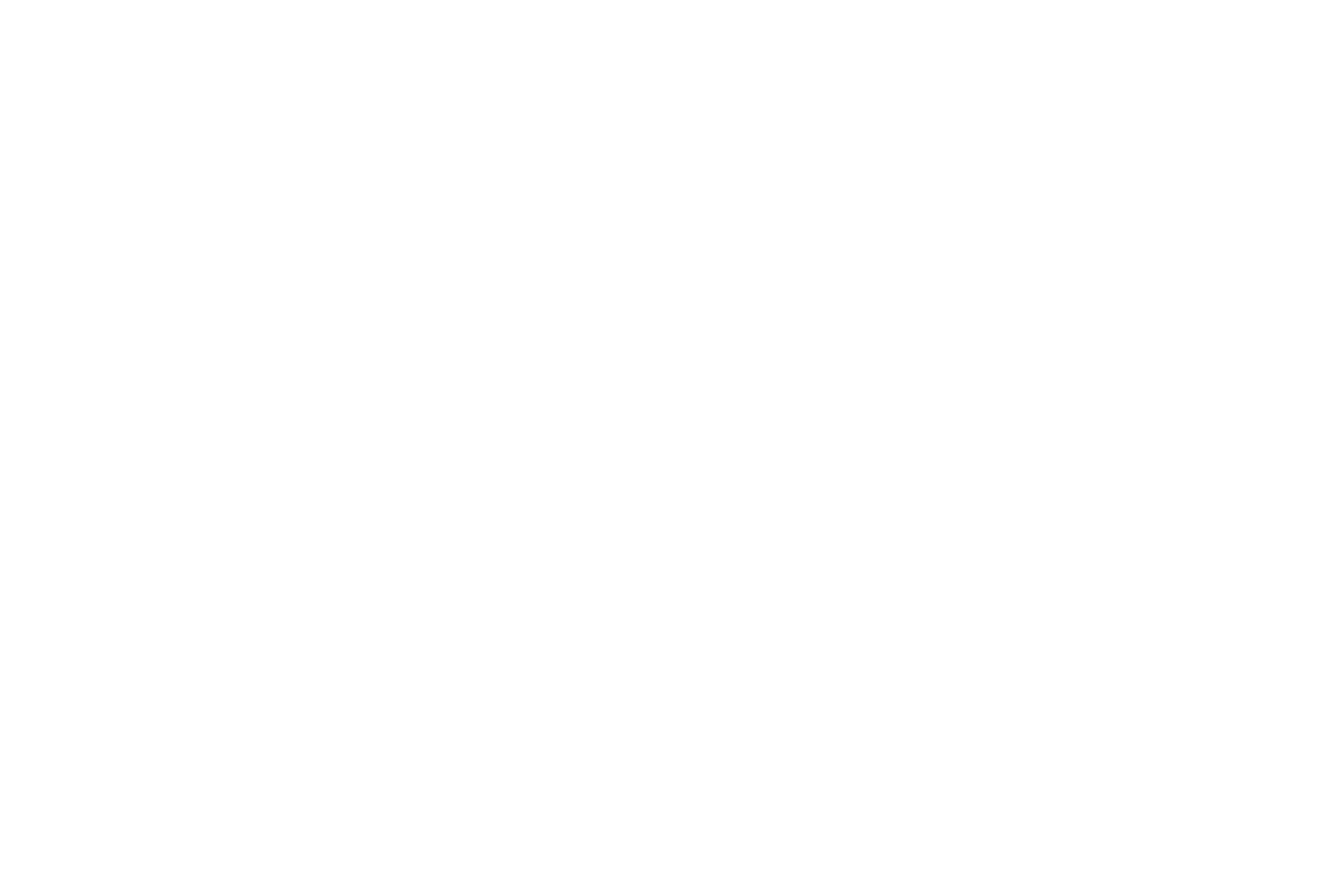

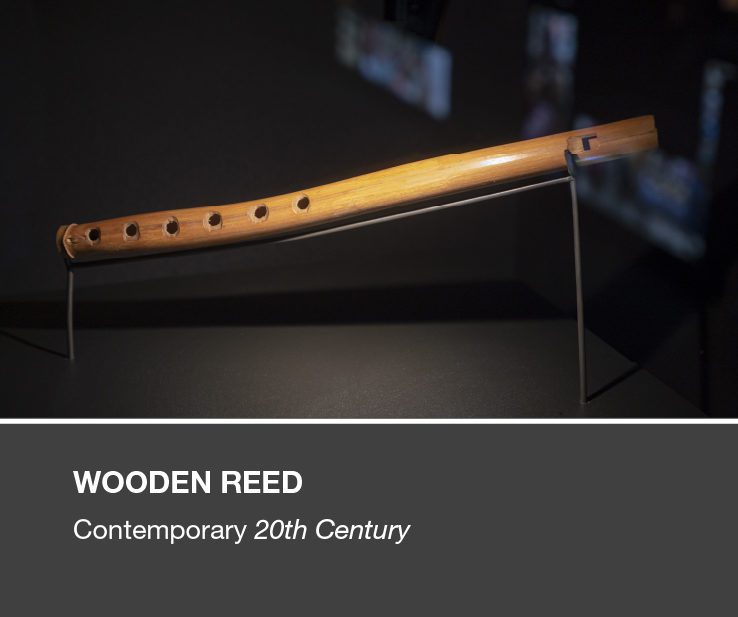

CONTEMPORARY MAYA

Maya culture lives on. There are 30 contemporary Mayan languages, all with a common root. The Maya continue to plant the heirloom seeds that sustained their ancestors. They create art, music and literature. They take part in rituals that are central to their faith. “Kawinaq,” they say. “We are still here.” Colonialism has threatened the Maya for 500 years, yet they retain a strong sense of identity.

Click on the video icon to explore more!

THANK YOU FOR VISITING!

We are proud to share the Maya story with you through Maya: The Exhibition: Daily Life & New Discoveries. To discover more about the Maya, we encourage you to reserve Maya: The Exhibition: Royalty, Art & Cosmic Balance

To experience our local past in-person, click the link below to reserve your tickets to the Cincinnati History Museum.

To discover more about the Maya, we encourage you to reserve Maya: The Exhibit: Royalty, Art & Cosmic Balance using the link below.