Quick Tips

Resources

Standards

- Welcome to Cincinnati Museum Center!

- Let's begin our Virtual Adventure!

- Quick Tips!

- Maya: The Exhibition

- Maya: The Exhibition - Video

- Adventure Roadmap

- Meet the Experts!

- Maya Timeline

- Section 1 - Cosmic Balance and Divine Kingship

- Section 1.1 - Gods and Goddesses

- Section 1.2 - Maya Ball Game

- Section 1.3 - Myth of the Hero Twins

- Section 1.4 - Divine Kingship

- Section 2 - Maya Art

- Section 2.1 - Jade

- Section 2.2 - Paintings

- Section 2.3 - Ceramics

- Section 2.4 - Sculptures

- Section 2.5 - Gold

- Section 2.6 - Music and Dance

- Section 2.7 - Textiles

- Section 3 - Writing, Numbers and Timekeeping

- Section 3.1 - Maya Writing

- Section 3.2 - Maya Stationery

- Section 3.3 - Maya Codices

- Section 3.4 - Maya Numbers

- Section 3.5 - Maya Timekeeping

- Section 3.6 - 2012 Myth

- Section 4 - Kawinaq - We are still here

- Section 4.1 - Contemporary Maya

- Section 5 - New Discoveries

- Thank you!

Maya the Exhibition II: Royalty, Art & Cosmic Balance is the second of two virtual field trips. In Maya II, marvel at stunning artwork, discover sophisticated calendar and number systems, and meet a pantheon of gods and rulers who balanced the Maya universe.

This exhibit is a cooperation with Museums Partner and Patrimonio Natural y Cultural, supported by the Ministry of Culture and Sports in Guatemala. Lenders of the objects are The National Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology and The Ruta Maya Foundation in Guatemala.

ADVENTURE ROADMAP

Immerse yourself in the genius of the Maya, an urban civilization that grew from the tropical rainforest. How did the Maya rule themselves, and what can their art, writing, and calendar systems tell us about how they viewed the universe?

Join Cincinnati Museum Center and researchers from the University of Cincinnati and University of Bonn to study Maya through stunning artifacts and intriguing finds.

Section 1.

KINGSHIP AND COSMIC BALANCE

According to Maya belief, gods created the world, kept social order and presented role models for human conduct. Discover connections between Maya gods, kings and competition.

Section 2.

ART

Art flowered during the 700 years of the Maya Classic period. Artisans worked in shells, obsidian, jade, silver and more. Explore beautiful Maya treasures.

Section 3.

WRITING, NUMBERS AND TIME

Ancient Maya script and calendars make up one of the great ancient writing systems. Discover how they wrote and tracked time.

Section 4.

KAWINAQ - WE ARE STILL HERE

Maya culture lives on. “Kawinaq,” they say. “We are still here.” See how the Maya retain a strong sense of identity and culture in our globalized world.

Section 5.

NEW DISCOVERIES

Breakthroughs from University of Cincinnati and University of Bonn researchers reveal details about how ancient Maya people perceived the world around them and managed their land, forest and water resources.

MEET THE EXPERTS GUIDING YOUR VIRTUAL FIELD TRIP!

Dr. Nikolai Grube

University of Bonn, Germany

Dr. Nicholas Dunning

University of Cincinnati, Ohio

Dr. David Lentz

University of Cincinnati, Ohio

Dr. Sarah Jackson

University of Cincinnati, Ohio

Dr. Christopher Carr

University of Cincinnati, Ohio

Mariana Vázquez Alonso

PhD Candidate, University of Cincinnati, Ohio

Rebecca Nava

Artist and Educator

Ana Lucía Sebaquijay

Teacher - Law Student / Kaqchikel speaker

COSMIC BALANCE AND DIVINE KINGSHIP

According to Maya belief, gods created the world, kept social order and presented role models for human conduct. Kings ruled city-states and lived in palaces and temples in their city centers. The Maya called their rulers k’uhul ajaw, or “Divine King.”

Deer God Lidded Vessel

Early Classic period: 250 to 600 CE

This skillfully painted pot from Tikal’s Mundo Perdido complex features reptile heads on the pot’s outer surface and lid. The body of a deer adorns the top of the lid. The head of the deer god Wuk Sip forms the lid’s handle.

GODS AND GODDESSES

According to the Maya, the ancient gods lived in eternal darkness ruled by the Lord of the Underworld. Divine Hero Twins freed the maize and cacao gods, allowing them to ascend to the human world. The maize god’s death and rebirth repeat in cycles, starting with the rainy season. When ripe, he is harvested and some maize kernels are returned to the Underworld (or planted), where the maize god will be reborn.

In the Maya world, nearly anything could become a sacred object. A tree could connect the heavens, human world and underworld. A pyramid could become a Maize Mountain, where living beings transform into gods.

To maintain the balance of the cosmos and satisfy the gods, Maya priests performed rituals with offerings of incense, tobacco or food. The most valuable offering was human blood, which priests made only during periods of crisis.

Death God Mosaic

Late Classic period: 600 to 800 CE

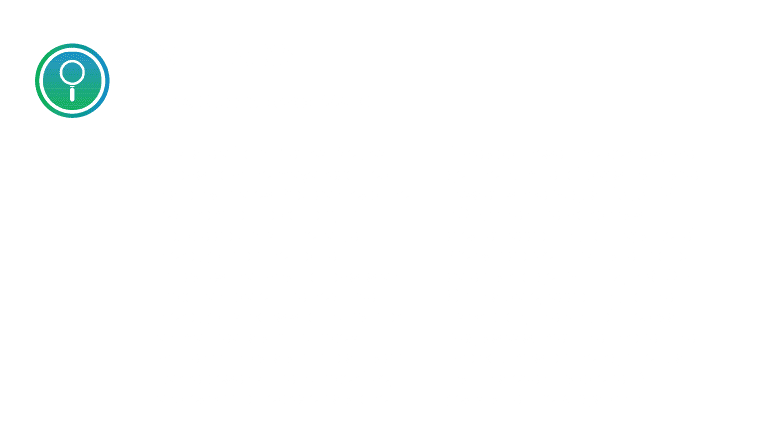

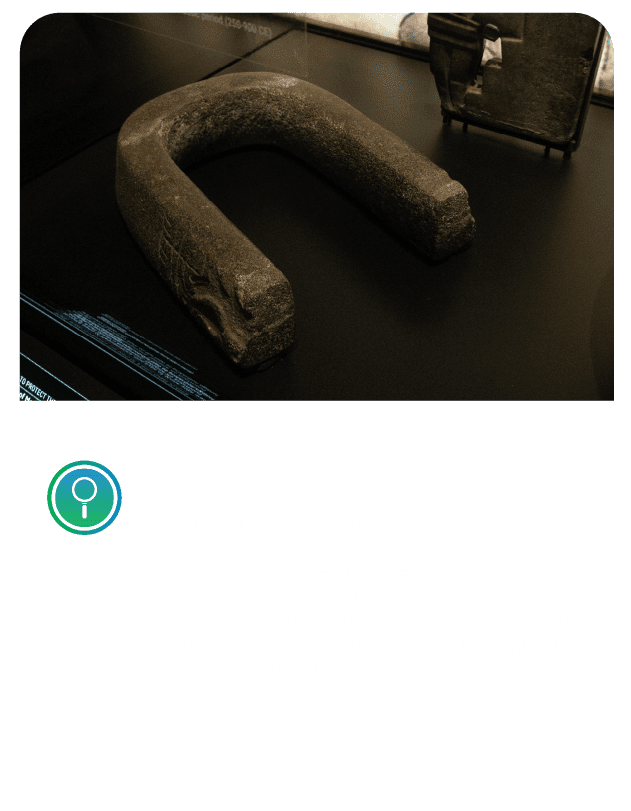

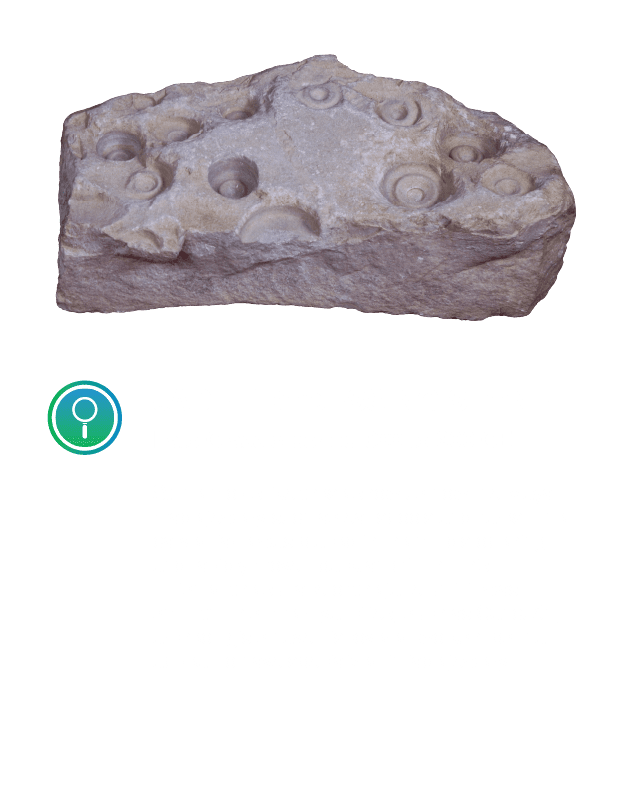

MAYA BALL GAME

One game played a part in the cosmic balance of the Maya world and appeared throughout Mesoamerica in the Classic period. Players hit a hard rubber ball between two teams on special courts. A team won by shooting the ball through a ring set into a wall of the court.

Almost every Classic Maya city had a ball court, usually located close to the royal palaces, temples and public squares.

To protect themselves, players wore special gear. Depictions of ballplayers wearing wide-brimmed hats or animal heads are common in depictions of warriors and hunters, indicating a parallel between the ball game, war and hunting. For the Maya, the ball game was an adventure—just as dangerous as a hunt or military campaign.

Image: Ballcourt adjoining the Great Plaza in Tikal.

Image Source: Simon Burchell - Wki Commons

MYTH OF THE HERO TWINS AND DIVINE KINGSHIP

The relationship between the ball game, hunting and war is based on the myth of the Hero Twins. The story starts with two brothers playing ball at the entrance to the Underworld. Harassed by the noise, the Lords of the Underworld called for the brothers to descend to the underworld and play ball against them. However, this was a trap and both brothers were killed.

After their death, a girl gave birth to twins who became mighty ballplayers. These “Hero Twins” were summoned to the Underworld, where the Lords defeated them, burned them and scattered their ashes into a river. Magically, they were born again. Jealous of the Twins’ magic, the Lords of the Underworld asked to be sacrificed themselves. The Hero Twins killed the Lords but refused to bring them back to life.

The Hero Twins’ father and uncle, the brothers from early in the story, were reborn as maize plants, connecting the ball game to the maize god.

On ball courts, athletes re-enacted the Hero Twins’ story and honored maize’s harvest cycle. Kings liked to be depicted as ballplayers because it linked them to the Hero Twins, showing them symbolically fighting the Underworld, helping the maize god’s rebirth and securing a good harvest.

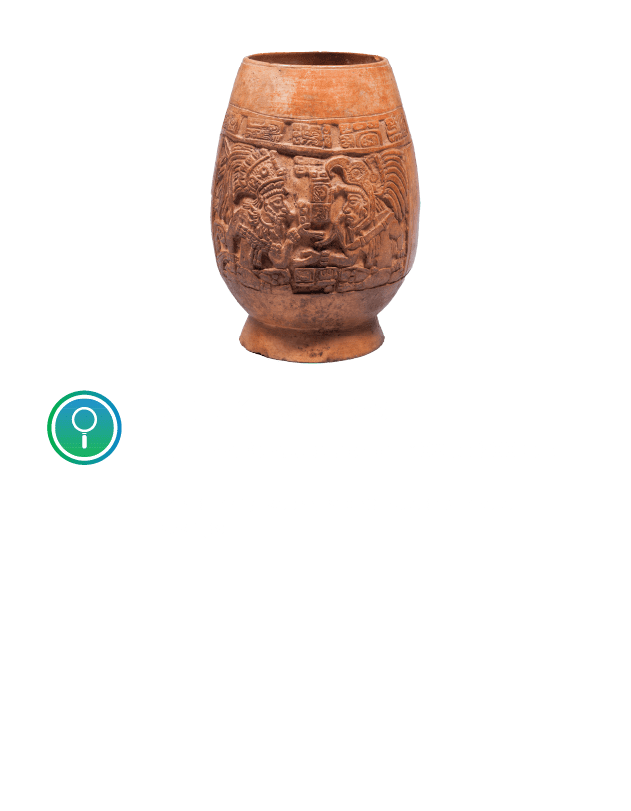

Painted Bowl Portraying the Myth of the Hero Twins

Late Classic period 600 to 800 CE

DIVINE KINGSHIP

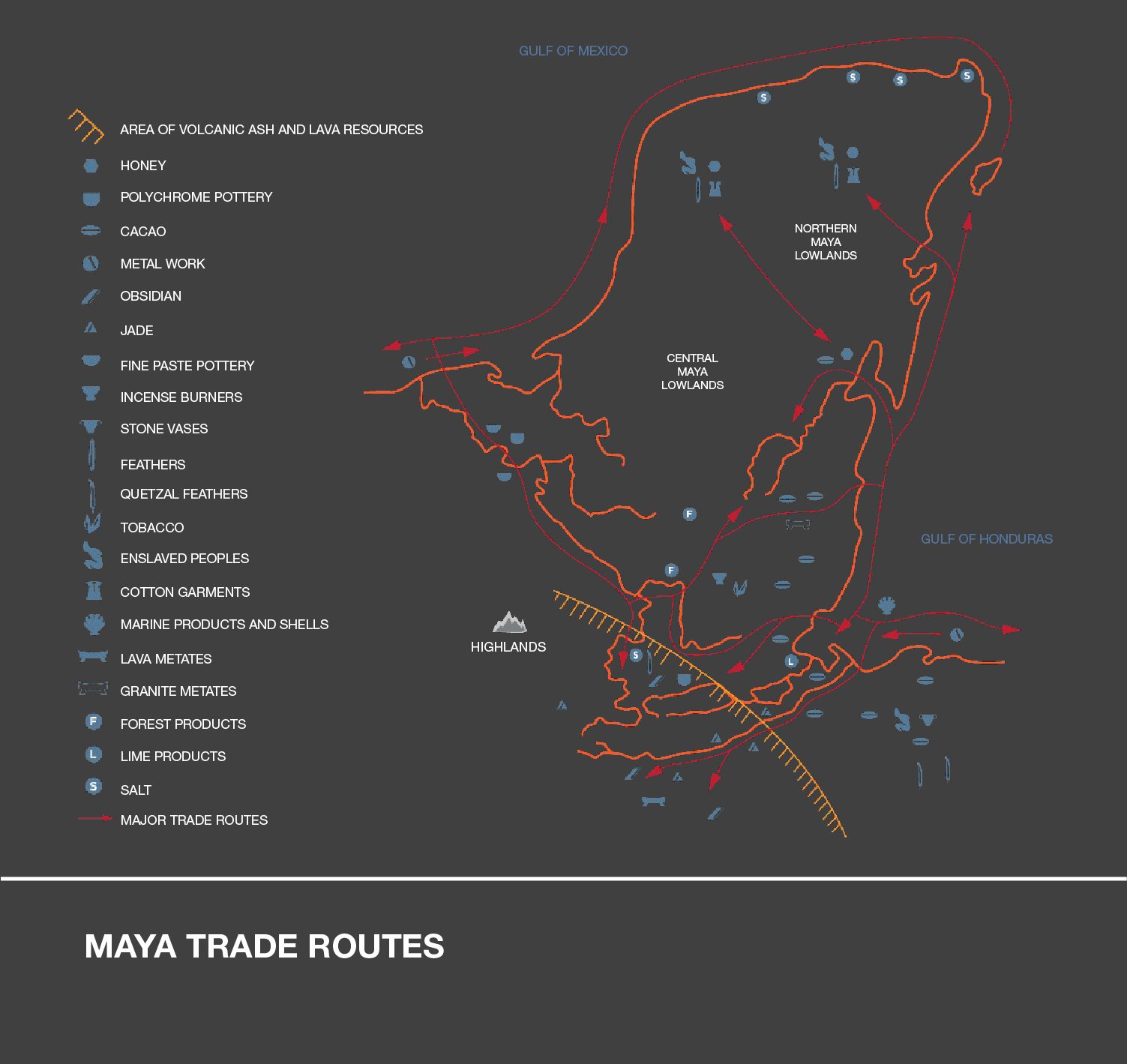

Although the exact number of small Maya kingdoms is unknown, each city-state had its own k’uhul ajaw, or “Divine King.” Kings mediated between human and divine worlds, created their own origin stories and claimed to descend from gods. They lived in luxury, trading long-distance for exotic goods such as obsidian, shells, pyrite and jade. Kings’ privileged access to food allowed them to live significantly longer than common people, whose average life expectancy was 25-35 years.

Religious worship drove Maya politics, and kings performed rituals to ensure cosmic balance. They also directed the labor force, raised taxes and controlled trade. Kings fought wars to gain wealth, hoping to loot and tax the cities they conquered.

As an embodiment of the maize god, the king wore jade jewelry, which represented fresh vegetation. When a king died, a jade mask was placed on his face.

Lidded Vessel with a Royal Portrait

Early Classic period 400 to 600 CE

MAYA ART

Art flowered during the 700 years of the Maya Classic period. Nobles and kings adorned their tombs with painted vessels, stucco portraits, carved obsidian mirrors and tiny clay figurines. While kings commissioned large public works of art, such as statues, stelae (large stone tablets) and temple murals, nobles often bought smaller artworks to wear or decorate their homes.

Maya artists and artisans came from every level of society. Many were elites themselves. Others were commoners whose talents led them to their crafts. For some Maya, all members of the family were involved, while others worked individually. Occasionally, elites competed to obtain an artist’s work. The Maya traded art throughout the region.

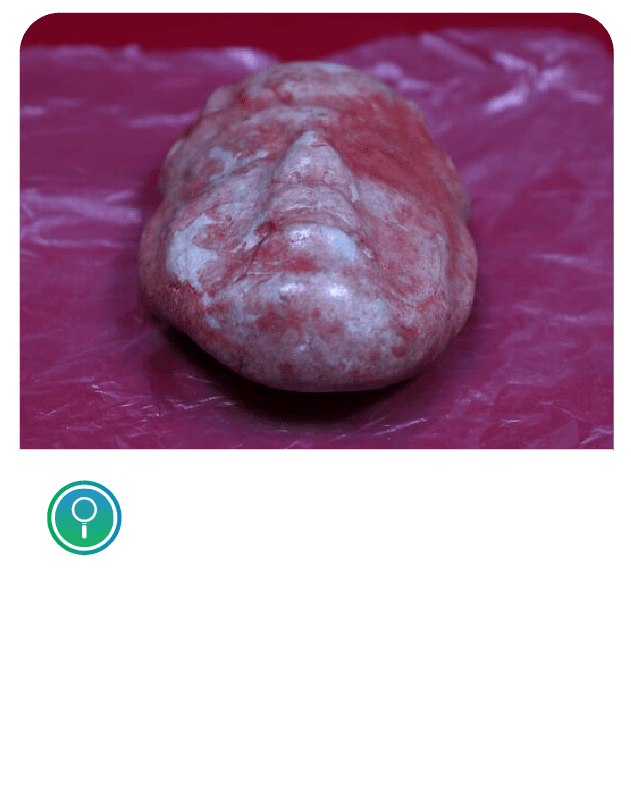

Carved Armadillo

Late Classic period 600 to 800 CE

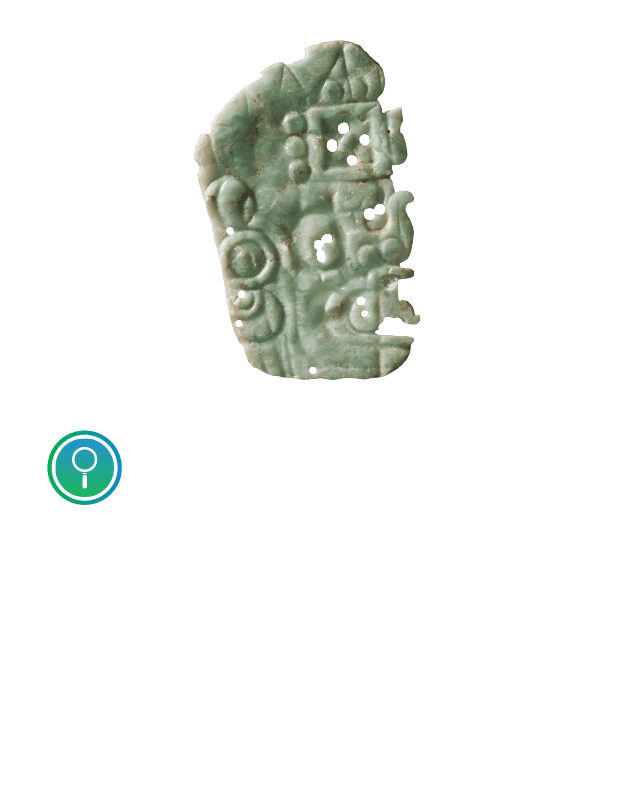

JADE

The Maya used masks made of jade and other green stones in the burials of kings and nobles. Jade’s green color symbolized vegetation, fertility and maize. Large jade masks covered the deceased's head, while small masks such as these served as belt or headdress ornaments.

Jade Ear Flares

Classic period 600 to 900 CE

A Closer Look!

CROSS-LEGGED KING JADE PLAQUE

Classic period 600 to 800 CE

This is one of the largest carved jade Maya plaques ever discovered. A Maya king sits on a throne, paying attention to a dwarf shown with crossed arms, the sign of greeting and respect. At the sides of the plaque, heads yield maize plants with emerging ears of corn, probably representing the young maize god.

A Closer Look!

JADE MASK

Classic period 250 to 900 CE

The eyes of this mask are inlaid shells with pupils made of obsidian. The lips are made from the inner shell of Caribbean oysters. Artisans polished jade plaques with water and sand to give them their shine.

PAINTINGS

Mesoamerica’s humid climate ravaged paints as well as textiles, but many Maya paintings survived in elite homes. Murals depicting the gods, nobles or even scenes from daily life cover walls, ceilings, arches and caves. Red and black colors were most common, but artists also used yellow and “Maya blue,” a bright turquoise color that the Maya invented and made.

Painted Vase

Late Classic period 600 to 900 CE

CERAMICS

Maya made pottery by hand and using molds. Artists selected clay, then added different elements like volcanic ash or limestone to create texture. Next, they covered the outside in minerals dissolved in water to provide color.

Ceramic vessels held daily food and drink and burial offerings in tombs. They provided artistic canvases, too. For Classic Maya royalty, vessels also conveyed their wealth and were used as gifts to arrange loyalty with local governors.

Urn with Jaguar-shaped Lid

Early Classic period: 250 to 600 CE

SCULPTURES

Maya artists sculpted from stone, stucco, bone, shell, fired clay and even wood, which rarely survived because of the humid tropical environment.

The most common subjects in Maya art are rulers and supernatural beings. Maya kings and queens employed full-time painters and sculptors.

Carved Tapir

Late Classic period 600 to 800 CE

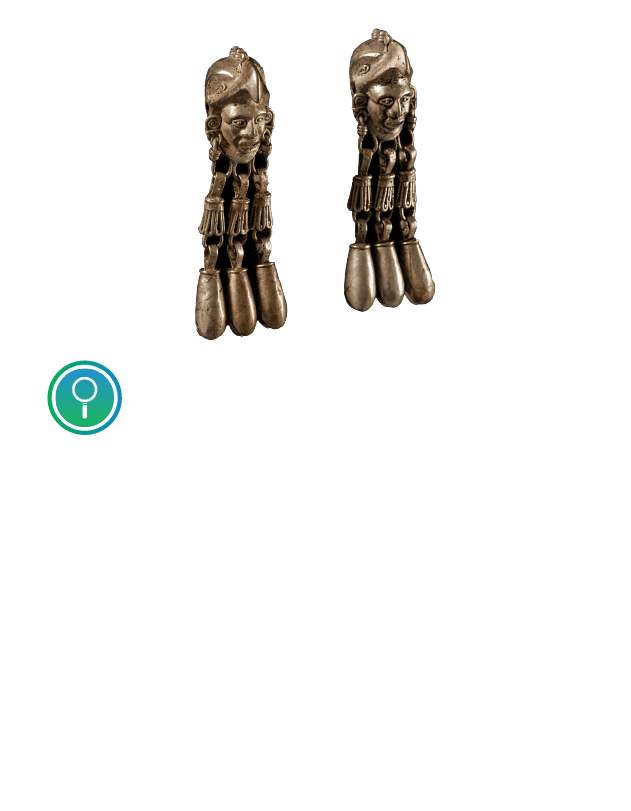

GOLD

Material culture changed considerably in the Postclassic Period, the time after the collapse of the big cities and before the arrival of Spanish colonizers. The Maya created new long-distance trade networks for goods and raw materials, including gold. Gold was rare during the Maya Classic period, but Postclassic Maya people gained access to it and learned how to process it.

MUSIC AND DANCE

Music is an important aspect of Maya culture and a key element of ceremonies and leisure activities. The Maya used wooden and ceramic drums, wind instruments and rattles at their celebrations and festivals. Some more complex instruments were reserved for the elite.

Drinking Vessel

Early Classic period 250 to 550 CE

Some archaeological objects of the Maya are musical instruments. This instrument makes a sound when water runs through the object.

Click the audio icon to hear the drinking vessel whistle!

TEXTILES

Click on the magnifying glass to learn more!

While most ancient Maya textiles have not survived, we see examples of them in statues and murals. Maya women were the main textile workers, weaving and dyeing fabrics—cotton, maguey cloth or wool—then embroidering or embellishing the cloth. While Maya clothing was generally simple, clothing decorations were not. Woven tapestries and brocades decorated homes as curtains and floor coverings. Maya communities had their own textile design that women wove into cloth produced there.

WRITING, NUMBERS AND TIMEKEEPING

Ancient Maya script is one of the great ancient writing systems, though its origin is still a mystery. The oldest archaeologically datable text was discovered on the site of San Bartolo, dating back to about 300 BCE, with a few hieroglyphs painted in black on stone. Maya script is probably several centuries older.

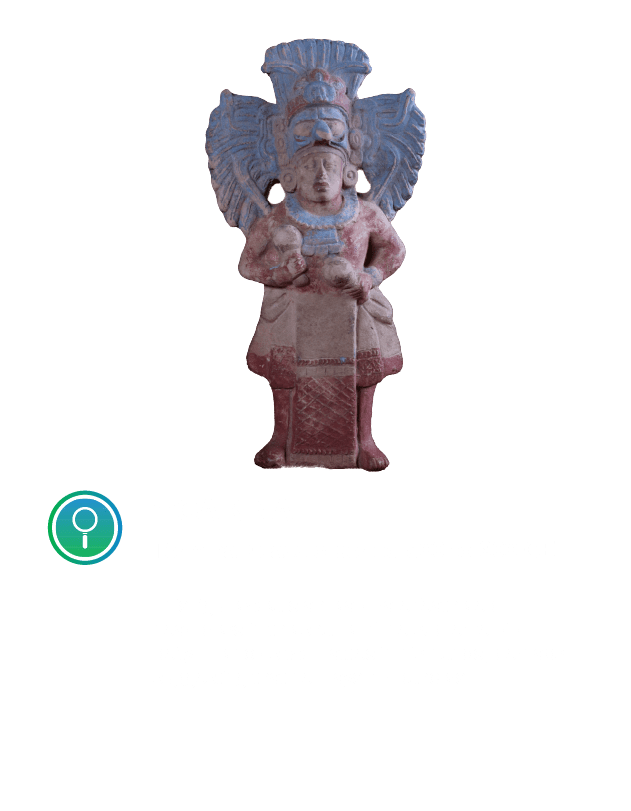

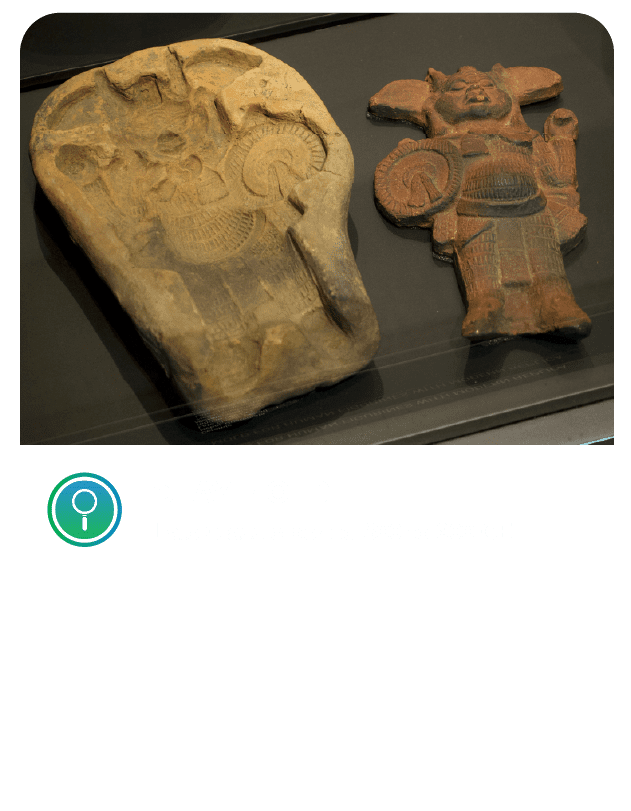

Ceramic Figures

Late Classic period 600 to 650 CE

Scribes had high social standing and were noble, living at the royal courts and often serving as priests.

MAYA WRITING

In past Maya civilization, reading and writing were mostly reserved for nobles and the royal court. While scholars and modern Maya people can now read most ancient hieroglyphs, likely only 10% of Maya in the far past were literate. Maya writing was highly advanced and expressed the complexities of Classic Mayan, the language spoken by nobles and priests.

Maya script consists of about 750 signs, or glyphs. Most glyphs represent an entire word; some represent just a syllable. Sometimes a syllable glyph will follow a word glyph to clarify pronunciation. Maya glyphs remained cryptic until the 1980s, when scholars finally deciphered them. Today we can read more than 70 percent of them.

Click on the video icon to explore more!

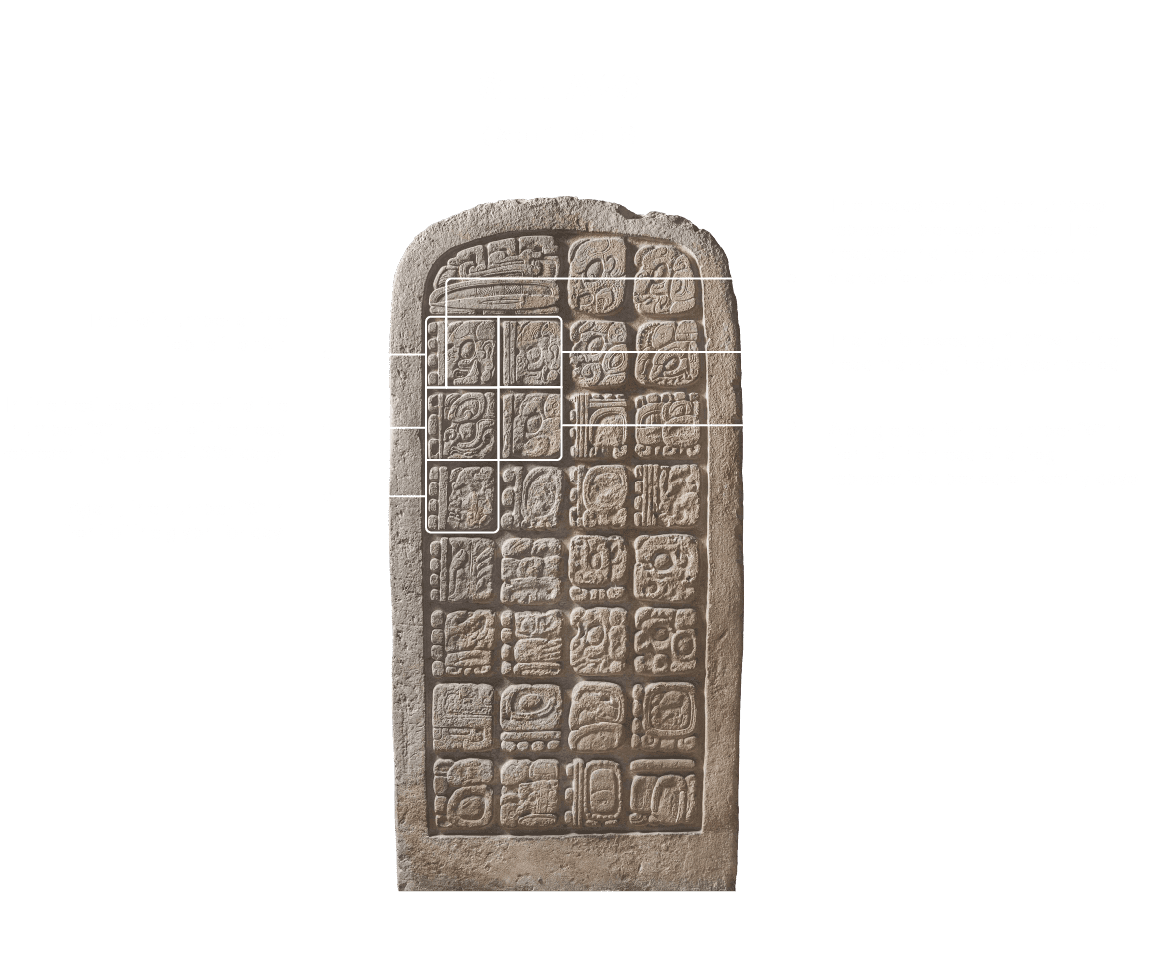

A Closer Look!

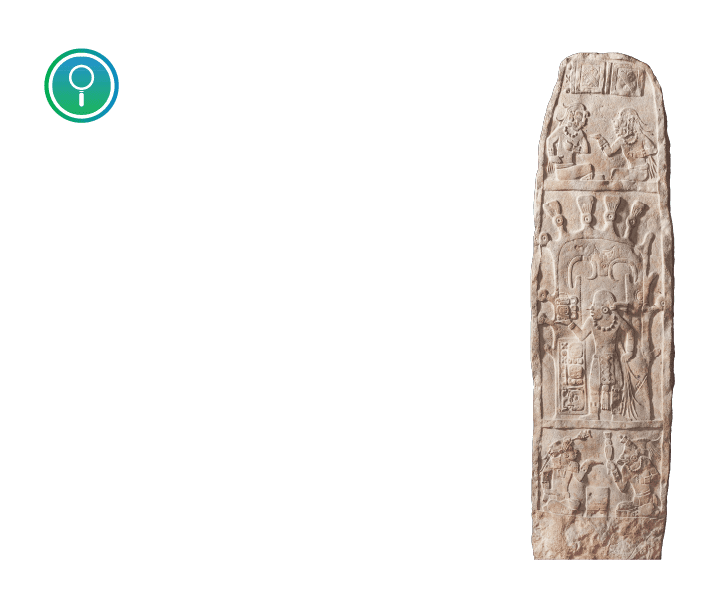

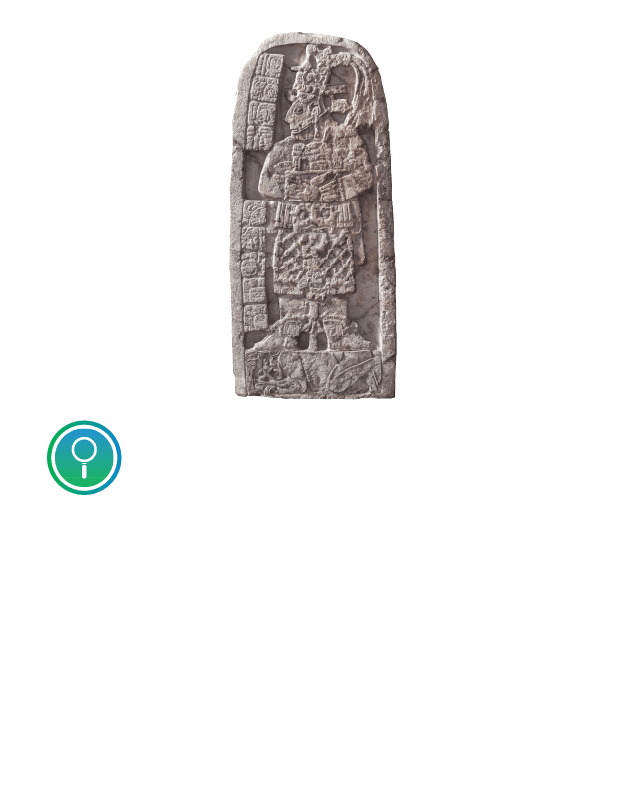

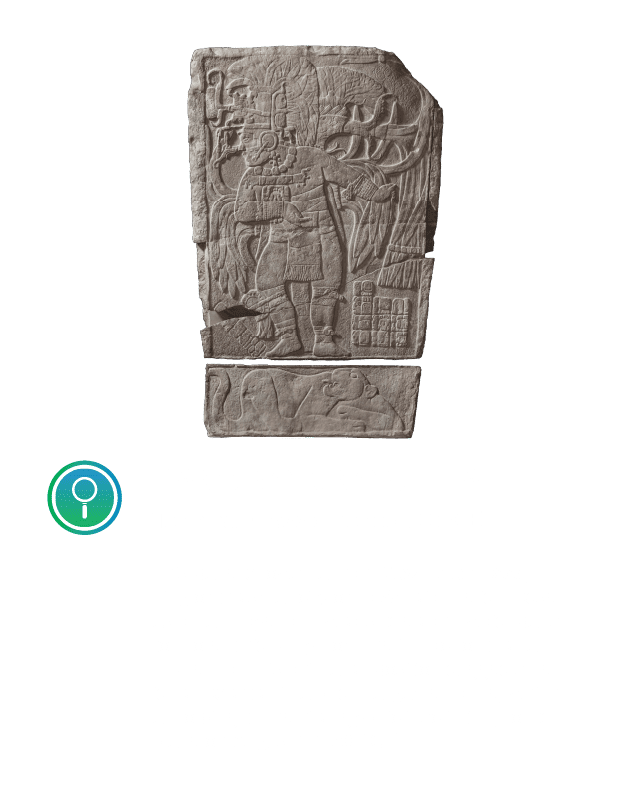

KING OF MACHAQUILA STELA

Terminal Classic period 816 CE

Artists and scribes created stelae (standing stones) to praise Maya kings and put them on public platforms. Stelae could share important news about wars, ceremonies and other events. This stela was commissioned by Siyaj K’in Chank II, king of Machaquila, to document his accession to the throne on April 4, 815 CE. The sentence “he tied the royal headband to his head” is followed by his name and numerous royal titles. The lower hieroglyphs record other events, including January 6, 816 CE, the day on which the stela was installed.

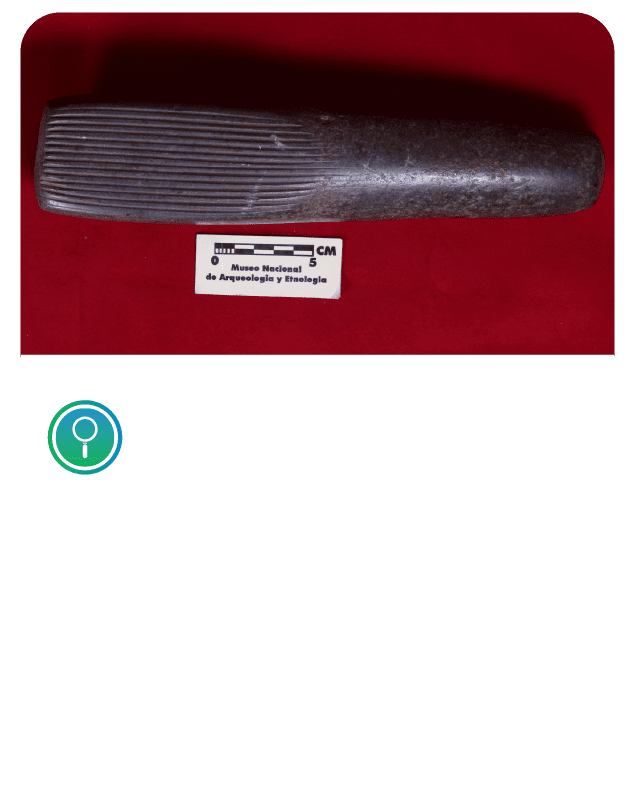

MAYA STATIONERY

The Maya matched their writing tools to their surfaces. They used stone or obsidian chisels to inscribe stone, and brushes to paint ceramics and paper. To make paper from fig tree bark, the Maya infused the bark with starch, pounded it into flat strips and whitewashed the strips with a fine layer of lime. Scribes wrote on every available surface: we find preserved texts on stelae (stone slabs), altars, lintels, stairways and walls. Text also survives on ceramics and jewelry, but rarely on wood in the humid climate.

Glyph Panel

Classic period 630 to 690 CE

The inscription mentions the ruler of Hix Witz, a royal dynasty based in Zapote Bobal and El Pajaral. They also mention Yukno’m Ch’een, the mighty king of Calakmul. The panel states that the king of Hix Witz is a subordinate of the king of Calakmul.

MAYA CODICES

Only four Maya manuscripts remain today, accordion-like books of inscribed bark paper. These extremely rare, precious objects are kept in Dresden, Germany; Madrid, Spain; Mexico City, Mexico; and Paris, France.

The Madrid codex is the longest, including chapters on beekeeping and agricultural rituals. The Dresden codex is the best preserved and contains astronomical tables, predictions, ritual instructions and a “who’s-who” of the gods.

The glyphs, numerals and pictures in these codices provide us with crucial clues for understanding Maya science. Tragically, in the mid-1500s CE, Spanish missionaries set fire to Maya books, which they considered the work of the devil. Flames destroyed knowledge acquired over 2,500 years.

MAYA NUMBERS

The Maya were masters of math. We use a base-10 system for mathematics, but the Maya used a base-20 system, with numerals ranging from 0 to 19. Numbers were written with only three signs: a dot for number one, a bar for number five and a flower sign for zero. Their early recognition of the principle of zero and its uses as a fixed quantity in calculations is remarkable.

MAYA TIMEKEEPING

The concept of time was important to the Maya, and their understanding of it was sophisticated. They combined several calendar systems to measure time and could measure in distance, as “feet” often noted as footprints.

One of the calendars, the Tzolk’in, was primarily used for rituals and divination and is still used by some Maya today. This 260-day calendar is based on 20-day signs, which are combined with the numbers 1 to 13.

The 365-day Haab calendar is based on the solar year, with 18 months of 20 days each, plus a month of five days. The two time cycles were combined to one, 52-year-long Calendar Round.

Since a Calendar Round date only happened once every 52 years, Maya chroniclers used the Long Count calendar to calculate all the days since the creation of the present world, beginning with August 13, 3114 BCE.

There is no evidence that Maya divided their day into units resembling hours, minutes and seconds.

Tripod Plate with a Date Glyph

Late Classic period 600 to 800 CE

The inner rim and the exterior of this plate are decorated with flowers from the cacao tree. In the center of the plate is the glyph for 13 Ajaw, a day of the tzolk’in calendar. Unusually, the glyph is written in reverse reading order, with the day sign placed before the number (Ajaw 13).

A Closer Look!

CAVE PAINTING

Painted in black on a stalactite, this ritual calendar scene shows two men holding small dots that spill from their fingers. The date, 9 Ajaw 3 Muwan, records the end of a 10-year period. Based on the painting’s style, the most likely Long Count date is 8.19.10.0.0, or February 1, 426 CE.

2012 MYTH

In 2012, popular culture latched on to a theory that the Maya predicted an apocalypse on December 21, 2012. This date corresponded with the end of an almost 400-year period in the Maya long-count calendar. Scholars argue that, while Maya astronomers saw each cycle’s conclusion as significant, they never foresaw an apocalypse. For the Maya, the end of the long count represents the end of an old cycle and the beginning of a new one.

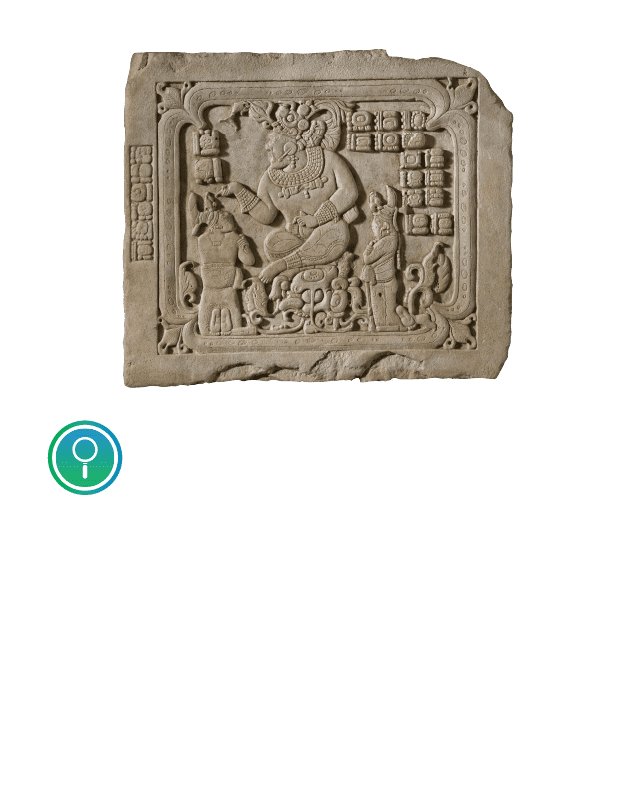

Panel depicting K’inich Yook, ruler of La Corona

Late Classic period ca. 677 CE

The inscription on this panel begins with a reference to the founding of the court of the Kaanul dynasty at Calakmul in 635 CE. At the end of the inscription, the text states that in 2012, the 13th bak’tun of the Maya calendar will be completed.

KAWINAQ - WE ARE STILL HERE

The close of the Classic Maya period meant the end of divine kingship and urban, courtly culture – but it did not mean the end of Maya people. The Maya survived great political and social transformations after their system of cities collapsed—just as they later survived the trauma of the Spanish invasion. Today, more than six million Maya descendants live in Mexico and Central America. Though they have lost their territories to industrial farming and mining, they move on, planting their seeds in new soil. Strong, resilient and adaptive, the Maya keep going. They have much to teach us.

CONTEMPORARY MAYA

Maya culture lives on. There are 30 contemporary Mayan languages, all with a common root. The Maya continue to plant the heirloom seeds that sustained their ancestors. They create art, music and literature. They take part in rituals that are central to their faith. “Kawinaq,” they say. “We are still here.” Colonialism has threatened the Maya for 500 years, yet they retain a strong sense of identity.

Click on the video icon to explore more!

NEW DISCOVERIES

Breakthroughs from University of Cincinnati researchers reveal details about how ancient Maya people perceived the world around them and managed their land, forest and water resources. UC’s innovative research techniques and fieldwork have helped us understand how the ancient Maya planned their cities, and why the Maya abandoned these sites in the 9th century. The work of UC researchers and their collaborators helps us understand ancient Maya culture and people.

Google Map: Identified are past and ongoing research projects, conducted by researchers from the University of Cincinnati.

Dr. Nicholas Dunning

Professor of Geoarchaeology & Neotropical Landscapes

“Many ancient Maya cities became victims of the so-called ‘reservoir effect.’ Urbanization was made possible by capturing and storing rainwater using increasingly sophisticated methods. Further population growth necessitated storing increasing amounts of water. Those large populations then became even more vulnerable when the region was afflicted with drought: the urban water supply was insufficient, and its quality declined.”

Dr. David Lentz

Professor of Biology and Executive Director of the University of Cincinnati Center for Field Studies

“Research at Cerén, a Maya village in El Salvador, showed that manioc was commonly used, but it was previously undetected because it doesn’t preserve well. The Cerén site, sometimes called the ‘Pompeii of Central America,’ was covered with volcanic ash around 600 CE. The ash preserved the houses, artifacts and even the agricultural fields amazingly well. As they were digging, the Cerén archaeological team found holes in the ash just before they reached the ground surface. When they filled these holes with dental plaster, it turned out that these holes were impressions of crop plants left in the fields. It turned out that there were extensive fields of manioc planted by the Maya, so it must have been an important food for them! This discovery has changed the way we think about ancient Maya agriculture.”

Dr. Sarah Jackson

Professor of Anthropology

“Studying the past is exciting because it challenges you to think about how life would have been different in another time and place. When I started to realize that the categories we use as archaeologists were not the same ones that the ancient Maya would have used to describe the same materials, I got really excited. This was an opportunity to use data, including texts and images, to reconstruct elements of how the ancient Maya experienced the world around them. The result makes the work of archaeology more inclusive of multiple perspectives!”

Dr. Christopher Carr

Research Assistant Professor of Geography

“One of our main geography questions is defining what the ancient Maya found attractive in bajos — these seemingly unattractive swamps. LIDAR makes it much easier to navigate this tricky terrain, and I, at least, don’t consider the swamps as forbidding as many of the old-timers led me to believe.”

Dr. Nikolai Grube

Curator of Maya: The Exhibition and Professor of Ancient American Studies and Ethnology at the University of Bonn, Germany.

WANT TO HEAR MORE FROM OUR EXPERTS?

University of Cincinnati colleagues share additional insights about their research and careers.

INCREASING DIVERSITY IN ARCHAEOLOGY

Dr. Jackson shares her passion for ensuring the field of archaeology features voices from women and multiple ethnic identities to define more well-rounded questions to answer questions about the past.

CATEGORIES: FLIP BOARDS

Dr. Jackson discusses how the Maya have both similar and different ways of describing objects and seeing the world.

CANCUEN KING PANEL

Dr. Jackson helps us imagine the steps from discovering an artifact to what we see exhibited in a museum.

CANCUEN GLYPH PANEL

Dr. Jackson shares how the act of drawing helped her look at the text differently and how she brings together information from multiple sources to advance new understanding.

GEOGRAPHERS ROLE IN ARCHAEOLOGY

Dr. Carr discusses how his role as a geographer complements the role of archaeologists.

RESEARCH IN A HOLE

Dr. Carr describes the work that takes place in the excavation pits of Maya reservoirs.

INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES

Dr. Carr discusses the importance of involving experts from multiple fields to support research.

STUDYING MAYA LIFE IN THE FOREST

Mariana discusses working with people familiar with the forest and with archaeologists to study how the Maya lived in the past.

THANK YOU FOR VISITING!

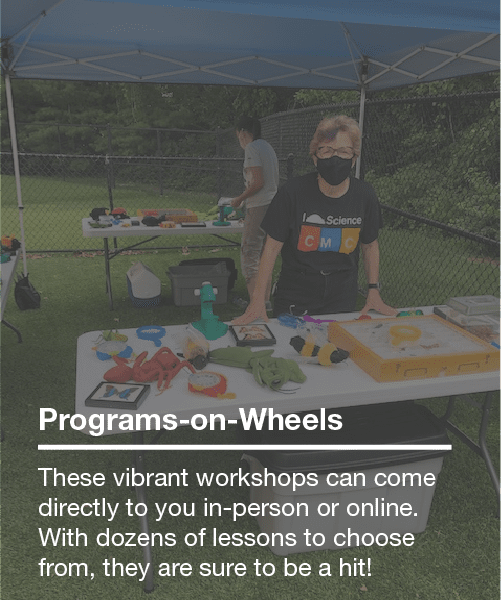

We are proud to share the Maya story with you through Maya: The Exhibition: Royalty, Art & Cosmic Balance. Be sure to check out CMC's other EPIC offerings by clicking on the links below.

To experience our local past in-person, click the link below to reserve your tickets to the Cincinnati History Museum.

To discover more about the Maya, we encourage you to reserve Maya: The Exhibition: Daily Life & New Discoveries using the link below.